The winter of 1939-40 [after the German invasion of Poland] was one of the longest and coldest in memory….It was as if all sides were waiting for a mediator to intervene and undo hasty deeds. Millions of Germans still believed that the British and French did not want to wage all-out war, despite their declaration of September 3. “The French could have beaten the hell out of us when we were busy in Poland,” said my Uncle Franz, who had recently become a member of the police. “Even they are not stupid enough to attack now when we face them in full strength. And don’t forget, our victory in Poland must have scared the hell out of them. No, they missed their boat for good.” But my grandmother merely snorted: “If it’s all over, why does this whole valley look like an armed camp?”

“Just propaganda,” replied my uncle disdainfully. “What would Hitler do with France anyway? He’s got a hell of a chunk of land now in Poland. That’s what he’s really after.” The craving for land was something my grandmother understood better than my uncle. “Hitler won’t rest until he has Alsace-Lorraine back,” she said calmly. “He always says the French stole it from us in 1918, and he’s right on that.”

[In Gymnasium]… Herr Fetten, the assistant headmaster whom we called ‘the cuckoo’, claimed that not even half of us incompetents would ever graduate. He didn’t know how right he was, if for a different reason. Over half of my classmates were killed before they reached the age of 18.

Despite its benefits, the Hitler Youth contributed to lower scholastic standards, since it claimed so much of our time and energy. Even before the war, two afternoon’s a week were taken up by rallies and frequent Sunday parades. As the fortunes of war turned against us, education suffered grievously, until it almost disappeared in its existing form after the summer of 1944. From then on, all boys over 15 could be called up for duty. Entire school classes were shipped to the front to dig ditches, man anti-aircraft guns, and finally fight the enemy in close combat. The portents were there in 1940.

In the early morning hours of 10 May, 1940, our troops swarmed across the borders of France, Luxemburg, Belgium and Holland. Woord War II had begun in earnest. The French expected to break our initial thrust at their Maginot Line, but General von Rundstedt’s panzers drove north through the difficult terrain of the Ardennes, for the moment by-passing the Maginot Line and rolling through Luxemburg into neutral Belgium and Holland. Paratroopers jumped deep behind the Dutch lines, sowing confusion and paralyzing resistance…. When King Leopold of Belgium surrendered his army on 28 May, without consulting with his allies, the British Expeditionary Force was given orders to evacuate Dunkirk…. After Dunkirk, no German doubted the outcome of the battle for France…. [Paris falls 14 June 1940] On that day, few Germans remained unimpressed by the feats of their Wehrmacht. My brother told me years later that my father chuckled with glee when he listened to the radio report describing the entry of our troops into the French capital, something no German soldier of 1914 had achieved. In the provinces bordering France, jubilation was unrestrained. The French were finally tasting the bitter fruit of the Treaty of Versailles which had subjected our land to 12 years of occupation….

By the summer of 1940, I seriously doubted I would be fortunate enough to fight. Only England remained to be defeated, and it was on its last legs due to the ever-tightening noose of our U-boats….Several of my classmates had already decided to become career officers, but I didn’t think the war would last long enough and I didn’t see much excitement in a peacetime army….

On morning my Uncle Franz and my grandmother took me to the synagogue, which had been turned into a prisoner-of-war camp. What took place next was almost like a slave auction. About two dozen farmers milled around in the backyard of the building, somewhat self-consciously inspecting 30 to 40 French prisoners. A German sergeant passed his helmet around and everybody took a number. That’s how we got George Dupont. [The French POW worked for nearly 5 years on Heck’s farm.]

Especially among farmers (who were always complaining anyway), it wasn’t at all unusual to hear jokes about Hitler, the other leaders, and the war in general. But the international ‘undermining of the will to fight’ by stating that Germany ought to surrender was an accusation that could draw the death sentence as early as 1941. Anyone careless enough to make such a statement after the assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944 was simply committing suicide. By then our parents and elders had become afraid of us and our single-minded fanaticism….

On a cold November evening, my grandmother called me into the milk kitchen next to the stable. “Come in here and say good-bye to Frau Ermann,” she said. If Frau Ermann was as embarrassed as I, she didn’t show it. I hadn’t talked to her for years outside of a quick nod when I saw her on the street. Her hair was totally grey and she seemed frail and shrunken, but she was quite agitated.

“I’m glad it’s finally over, Frau Heck,” she said. “Maybe we’ll get some peace now, since they don’t want us here anyway.” Rumors had been afloat that the Jews of Wittlich would all be deported since we were located in the defenses of the Westwall, but I couldn’t quite see why they would spy on us now after the defeat of France. “We’ll be gone in four days,” said Frau Ermann, and then she broke down and started to sob. My grandmother reached out to her and pulled her to her chest. “Get out,” she hissed at me. I had known that she still lit Frau Ermann’s Sabbath fire, despite Uncle Franz’s mild protestations, but this was the first time I had seen Frau Ermann come into our house. My grandmother did not invite easy intimacy and nobody called her by her first name, but I heard her say to Frau Ermann, “It’ll be alright, Frieda. All of this madness is going to pass.”

I never did say good-bye to Frau Ermann, and I was relieved I didn’t have to. When I told my grandmother the Jews would be shipped to Poland to atone for their crimes by working the land, she shrieked in a rage, triggered by her own feelings of shame: “How would you like to work as a slave on a lousy farm in god-forsake Poland, Du dummer Idiot? What have the Ermanns ever done to us?

The Jews of Wittlich were not herded into cattle cars. There were perhaps 80 of them left. One morning early, as I came home from serving Mass, I saw a small group of them guarded by a single SA man, walking toward the station. Jews had become lepers. All were dragging heavy suitcases. Many frantically sold their valuables at sometimes ridiculous prices. All Jewish property became the trust of the government. My grandmother bought stacks of Frau Ermann’s fine linen, and stored three boxes of her silver and other valuables in our wine cellar. That was against the law, and I only found out about it when I overheard her discussing it with my uncle. “My God, mother,” he said, “Don’t you realize you could end up in a KZ for that?”

… Although the principal function of the camps was to contain and punish political opponents, or indeed anyone who dared to criticize the government publicly, criminals, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses and Gypsies were also sent. The name that covered all of these categories of offenders was Volksschädling, “parasite of the people.”

By 1938, the Gestapo had become all powerful and was beyond the control of the regular judicial system. A man convicted of three burglaries, for instance, might be sentenced to five years in prison. Since it was his third offense, the Gestapo might well meet him at the courtroom door and lead him away. There was no appeal against such action. What made the so-called ‘protective custody’ of the camps even more terrifying was the uncertainty. I person might be kept for years, suddenly released, or simply executed. A sentence was usually not pronounced in public.

When the Jews left Wittlich in three third-class cars, few guessed that they might go to a concentration camp. Prior to Kristallnacht of 1938, most camp inmates had been non-Jewish. Most townspeople, myself included, did not doubt that the regime would deport them to Poland, into the enclave known as the General Government. For years, the Nazi regime had proclaimed to us and the world that it wanted to make Germany judenrein, clean of Jews…. The ‘Final Solution’ to exterminate was decided upon at a small, top-secret conference in Wansee, a suburb of Berlin. The year was 1942, and the SS had captured millions of Polish, Russian, and other Eastern Jews. That incredible, incomprehensible decision to wipe out a whole race was always kept secret from the German masses. To us in the Hitler Youth, the Final Solution meant deportation, but not annihilation. A measure of guilt must go to most Germans because they neither disputed, nor opposed that decision. We in the Hitler Youth wholeheartedly approved, although nobody asked our opinion. Despite their newly-found conscience after the war, most citizens of my hometown felt the same….The notion of Auschwitz as a farm seems grotesque now. It was perfectly believable to me in 1940.

It’s strange how casual we took our new enemy, the United States, at that time [early 1942]. Goebbels ranted that our U-boats would take care of American war and supply ships making their way toward Europe…. In the Hitler Youth we shared the regime’s belief that America was much too soft to take us on in addition to the Japanese…. The British were, we assumed, finished as a world power and only existed because of the American lifeline. The Soviets were the key to our victory. All we had to do was to hold on during the harsh winter and then to hit them full strength with the first thaw. No nation, we were told, could survive the staggering losses of men and territory that the Russians had. We knew that measured by the ferocity of the battles before Moscow, it would be a bloody spring. Hitler’s monumental misunderstanding of the American war potential, as well as the will of its ‘soft’ people to fight was shared by many Germans who should have known better….

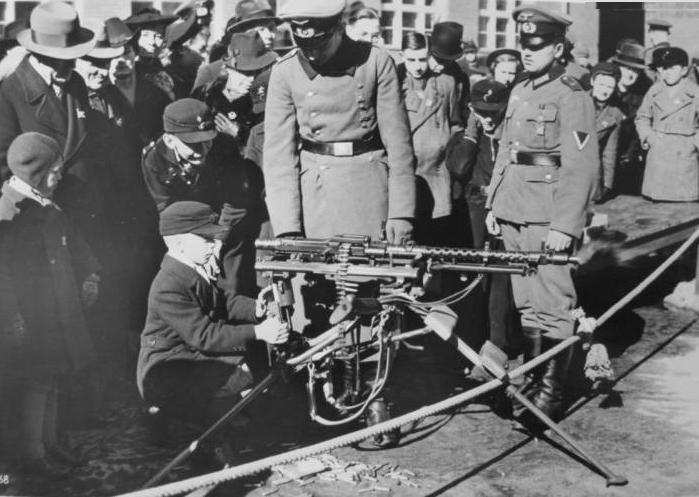

At 14, we left the Jungvolk and were sworn into the senior branch, the Hitlerjugend. That usually took place on Hitler’s birthday, April 20…. Nearly 70% of the roughly 180 members of the Gefolgschaft [the flying section of the Hitler Youth] were Gymnasium students, thus making it almost an extension of our school. The Luftwaffe took nearly all of its pilots from the Flying Hitler Youth and had to insist on a fairly high level of education as well as superb physical fitness. We were trained by officials of the National Socialist Flying Corps [NSFK], which was an auxiliary of the Nazi Party. Above it stood the Luftwaffe, which considered us its pool of future manpower. Three days before our Easter vacation, I received a registered letter from the headquarters of the Hitler Youth, ordering me to report to the glider camp Wengerohr, a Luftwaffe base just four miles south of my hometown, now principally used to train glider pilots. I was ecstatic at the news….By the fall of 1942, Nazi Germany stood at the pinnacle of her power. If one looked at a map of Central Europe, the only countries which hung on to a precarious neutrality were Sweden, Switzerland, Spain and Portugal. From the tip of Norway to the shores of Africa, from the British Channel to the Volga, extended the largest German Empire the world had ever known. It was a promising time to be a young German. Final victory was already assured and only a glorious death on the battlefield might cut short our nearly unlimited future. Yet, unknown and unbelieved by most of us, the winter of 1942-43 carried the seeds of our destruction…. The Hitler Youth began to step up its pre-military training, often under the guidance of Wehrmacht [regular Army] non-commissioned officers. Rifles were nothing new to us — from the age of 10 we had been instructed in small-caliber weapons — but this was different. We spent most of the day on the rifle range, handling the standard Wehrmacht carbine with its sharp kick, as well as the 08 Pistol, the 9mm handgun our foes called the Luger. We also learned to throw hand-grenades and fire bazookas at tanks. Finally during the last two days of the course, we were introduced to the MG-41, a machine gun capable of firing 1000 rounds per minute.

… Gert Greve was my Gymnasium classmate and had recently received his B glider rating at a different base. Gert, who was tall, heavy set and so blond that his hair seemed almost white, was very good at mathematics, my Achilles heel, but had a hard time with foreign languages, which came easy to me….Gert and I often served Mass together in the hospital chapel, which must have been an odd sight since I was black-haired and of medium height, while he looked like a Teutonic knight. The SS officers who wanted to enlist us when we were still only 15 were drawn to him like priests to Rome. “You could become a stud in the SS with your ideal Nordic looks,” I often teased him with a touch of envy….

… Gert Greve was my Gymnasium classmate and had recently received his B glider rating at a different base. Gert, who was tall, heavy set and so blond that his hair seemed almost white, was very good at mathematics, my Achilles heel, but had a hard time with foreign languages, which came easy to me….Gert and I often served Mass together in the hospital chapel, which must have been an odd sight since I was black-haired and of medium height, while he looked like a Teutonic knight. The SS officers who wanted to enlist us when we were still only 15 were drawn to him like priests to Rome. “You could become a stud in the SS with your ideal Nordic looks,” I often teased him with a touch of envy….

It was the pomp and paraphernalia, especially the flag worship of the Hitler Youth, which instilled the belief in us that we belonged to the chosen ones, the future leaders of our country….

CHAPTER 5

By 1943, Hitler Youth leaders were young, since none served until they were eighteen. A year later, many Gymnasium students were being drafted at sixteen as a result of our tremendous casualties…. Closer to Wittlich [Heck’s hometown], the beautiful city of Cologne had just experienced its first 1000-bomber raid, but the most persistent target was the industrial Ruhr, traditionally Germany’s weapons forge. … In 1943, I thought it unlikely that the enemy would ever dare land on the shores of Festung Europa [Fortress Europe]. It was a shame that our cities had to be turned into rubble in these “terror raids” as Joseph Goebbels called them. But just as our raids on London had never broken the morale of the British people, the Allied bombings never shook ours. On the contrary, it made it easier for Goebbels’ propaganda machine to convince the people that they were in for a merciless fight to the finish.

… Our Axis partners had never been held in high esteem for their fighting qualities, even at the beginning of the war. They hadn’t been able to conquer Greece without our help. The Wehrmacht had to bail them out in 1941, which delayed Hitler’s attack on Russia by a crucial five weeks. It may have cost us the conquest of Moscow. By 1943, when much of their army was turning against us, a Hitler Youth leader would sooner be called a Bolshevik than an Italian. Bolsheviks at least had the guts to fight….

CHAPTER 6

For my family the war began to get grim only a few days into 1944, which had been proclaimed by the Hitler Youth as ‘The Year of the War Volunteer. That was rather a joke: we were ordered to volunteer. Uncle Gustav was suddenly transferred to the Eastern Front…. In January of 1944, the Russians began to attack from the Leningrad sector, and Gustav’s brigade was throne into the gap. The Soviet assault was stemmed temporarily, but 80% of the brigade had been wiped out. Gustav was listed as missing-in-action…. In the savage fighting of the Eastern Front both sides slaughtered their prisoners at whim. SS soldiers in particular, neither gave nor expected quarter. Rather than surrender, they usually committed suicide in a hopeless situation. Most had an agreement with their buddies to shoot each other in case they were severely wounded and could not be evacuated. …

By early 1944, the Nazi empire had shrunk under the concerted attack of our numerically superior enemies…. Not even the most brilliant propaganda could gloss over our enormous losses. Joseph Goebbels did not try. On the contrary, he staged a mammoth rally in Berlin in which he exhorted the carefully chosen audience to choose either death or victory. “Do you accept total war, people of Germany, or annihilation by the hands of the Soviet-Jewish beast?” he shouted repeatedly.

“We want total war,” roared the crowd, not surprisingly. From then on, anything not essential to the war effort was sharply curtailed. Only the very basic consumer goods such as pots and pans were produced. Movie houses closed and tens of thousands of housewives ended up in ammunition plants. Eventually, over four million foreigners [mostly from Eastern Europe; many Jews] were sent to do slave labor in our factories.

At the core of the domestic effort was the Hitler Youth. Since 1943, whole Gymnasium classes with their teachers had been put into uniforms and trained as Flakhelfer, auxiliary units to man anti-aircraft batteries within Germany. That happened to the class above me in 1944…. During Easter vacation of 1944 I was ordered to attend a special weapons training camp run by Wehrmacht officers….

Rabbit [Heck’s best friend in flight training] and I had every reason to believe that the Luftwaffe would call us up within weeks. We were 16, ready and more than eager for fighter command. Roman [another of Heck’s friends] found this slightly amusing. “Are you two children aware that the life expectancy of a green Luftwaffe pilot is all of 33 days?”

[After the Normandy invasion, Major-General Wendt o fthe Hitler Youth organization gives Heck command of a unit of about 200 armed Hitler Youth, mostly made up of 15 year olds, and assigns him to the Luxemburg frontier as part of the defense of Germany’s so-called Western Wall.]

He opened his desk drawer and pulled out a new, automatic Walther 7.65mm pistol. “Here, that’s your first piece of armament, a gift from me… lease remember one thing: if you ever let me down, you’d better use it on yourself.” He shook hands and escorted me to the door. He stopped me again. “you’re going to have a bunch of pretty wild boys on your hands and you must never allow any breach of discipline. You are, in fact, in a war zone. You can have people shot, if you deem that necessary.” He wasn’t joking…. From that moment on I became a professional, salaried leader of the Hitler Youth. Money, however, was not the slightest concern to me. Power was infinitely more seductive.

[Heck moved his unit into a small village in Luxembourg, where he confiscated a school and convent to use as his barracks.]

… By noon we were all settled in. There was no open defiance except from on eof the three teachers, an elderly man who was the principal…. “This is illegal,” he shouted. I can’t allow this at all. By whose authority are you acting?” Liewitz [a lieutenant in the Wehrmacht] pointed to me and said, rather kindly, “I’m afraid the Hitler Youth is in charge on that.”

“This is just a boy,” raved the man, shaking a finger at me. I wasn’t used to anyone defying an order, least of all a Luxembourg schoolteacher who was intent on hampering the war effort. I motioned to Roman and Rudolf Kistner, another Scharführer [sergeant] who stood waiting behind me. “Throw this man out,” I ordered. “If he comes back, shoot him.” The man’s eyes widened as Roman and Rudolf grabbed him and he began to shake….

It was astonishing how fast young boys matured under pressure and unrelenting duty. Most of them acted like hardened men. Many had already lost a father or brother in battle and they were inured to the possibility of death. I had lost any apprehension about my ability to command effectively. Secretly, I enjoyed the power I wielded…. Roman was my closest friend. Yet I would have sent him unhesitatingly to a punishment camp for failing to carry out any of my orders.

You must be logged in to post a comment.