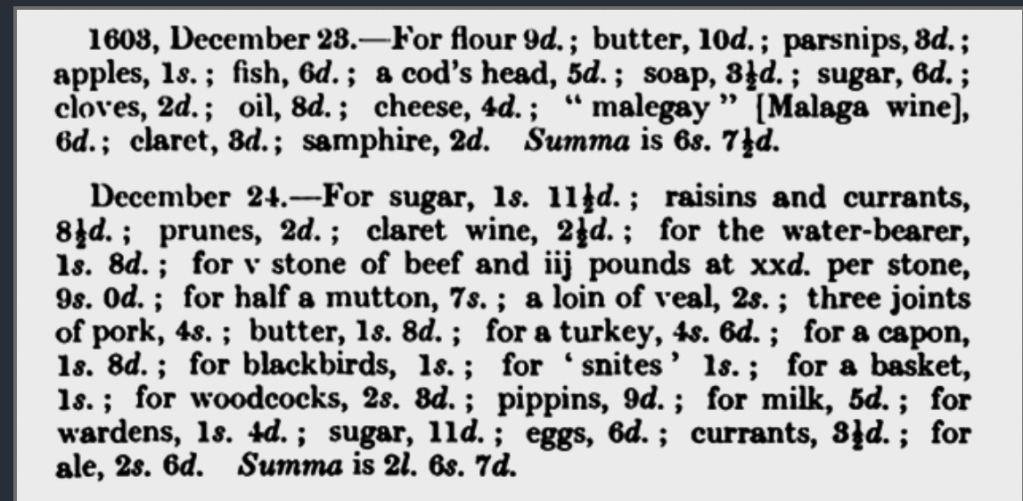

On December 24th 1603, at England’s first Jacobean Christmas, Mrs Elizabeth Cranfield, wife of merchant Lionel Cranfield, recorded the household expenses for the day, which were much higher than usual, presumably reflecting the preparations for the next day’s Christmas feast. Pride of place, and the most expensive item on the shopping list, was a turkey, sitting beside the capon, blackbirds, ‘snites’ (snipe?), woodcocks, beef, mutton, veal and pork on the day’s menu.

Turkeys had been introduced to England from the Americas only fifty-three years earlier, and were more usually called ‘turkey-cocks’ or ‘turkey-hens’. Exactly why they came to be named for the country Turkey is not clear, but the mistaken belief that turkeys came from the vaguely defined ‘east’ was shared across most of Europe, hence the French word ‘dinde’ (‘d’inde’, ‘from India’), ‘indyushka’ (Russian), ‘indyk’ (Polish and Ukrainian) and ‘hindi’ (Indian) in Turkey itself.

Portuguese almost wins the accuracy prize, naming the turkey ‘peru’ and hitting correctly on the Americas as the turkey’s land of origin. Unfortunately it falls at the final hurdle by suggesting a country in South America, rather than north, where wild, domesticated and occelated turkeys all originate.

Mrs Cranfield was certainly far ahead of the Christmas fashion, albeit there is evidence of turkey being eaten by Tudor aristocrats. But turkey as a mainstream food only arrived with the railways, which negated the need – this really happened – to ‘drive’ scores of turkeys long distances by foot, for which journeys they were sometimes outfitted with leather boots to protect their feet. For most Britons, turkey only became an affordable option and a Christmas tradition after the Second World War.

Image from Medieval and Early Modern Sources Online, Calendar of the Manuscripts of Major-General Lord Sackville Preserved at Knole, Sevenoaks (HMSO, 1940), p. 72.

You must be logged in to post a comment.