I doubt seriously whether a man can think with full wisdom and with deep convictions regarding certain of the basic international issues today who has not at least reviewed in his mind the period of the Peloponnesian War and the Fall of Athens.

George c Marshall

SUMMER ASSIGNMENT 2025: Read Landmark ‘Thucydides’ Books 1, 2, and 3 (to p.219)

When you read, have your pen and journal out for annotation. Overall, you should strive to keep enough notes that allow you to engage in serious discussion of the text at a later date (for us that is in September). Do not skip the introduction. Woodruff provides important information about the text and arguments about it. There are special sections below that address different chapters in Woodruff. It’s important that you approach your reading with some intention.

Remember that we are using the Landmark edition which you may access HERE. In the Fall we shall read and talk through the entire book, but you should front-load by reading Books 1,2, 3 this summer.

NOTE: read Book One particularly closely as Thucydides lays out his central thematic elements of the entire text here. You should try to identify them — write them in your notes! — as you go along.

Thucydides inhabits a unique place among ancient historians. As a writer he was an astute, ambitious innovator who set new goals for inquiry (‘historia’) into past events. Even though Herodotus gets credit as the ‘first historian’, it is Thucydides who established some of the core elements of the discipline. For one, although he does not cite them, Thucydides relied solely upon sources (including himself, since he lived through the events about which he writes) and was scrupulous about accuracy. He neither accepted nor rationalized Greek myths. He also sought explanations of causation in nature and men, not in the gods, nor in prophecies like many of the great authors before him, most notably Homer and Herodotus. Unlike Herodotus, therefore, he doesn’t fabricate claims and he leaves the gods (incluing fate/fortune) in their heaven. Thucydides is both founder and one of the greatest thinkers in the discipline of history; he established historical writing in ways that still define the field.

Thucydides, born between 460 and 455 BC, was an Athenian aristocrat who came of age in the era following the great Persian Wars, during the time of the Athenian statesman Pericles. He was in his twenties when the Peloponnesian War began and died a few years after its end in 404 BC, and left his account of the war unfinished. It is important to know that in 424BC Athens elected Thucydides as one of its ten strategoi, military generals, in the polis but exiled him soon after for his failure to defend the city of Amphipolis from the Spartans. This means that Thucydides was close to the action in the war about which he writes. He knew what was at stake. He knew the chief personalities. He understood the so-called zeitgeist. He had iron in the fire.

Thycydides writes of a specific war between two states — Athens and Sparta — and their allies. [CLICK HERE to read another entry I started about his writing on war.] The text, however, is equally a story of diplomacy, of the relationships among Greek city-states, of cultural values, of arguments and ideas, of the plans of men, their personalities and strategies for achievement. In the end, as Perez Zagorin asserts, Thucydides’ text is an account “of the human and communal experience of war and its effects.” While all readers are not equally interested in the details of Peloponnesian War per se, we read Thucydides today to acquaint ourselves with his mind, to wrestle with his ideas about causation and about politics rather than simply to digest facts. When you read, then, try not to get caught up with the details, but rather try to discern what Thucydides wants to say about the deeper structures of statecraft or human behavior. Take notice of what resonates with the affairs of men in 2023.

The historian, claims Donald Kagan (probably the leading scholar of the Peloponnesian War who just died last year), has the dual responsibility of seeking the truth of what has taken place and then of interpreting the events with wisdom and understanding. Thucydides sought to understand the behavior of man in society, in a word POLITICS, i.e. men engaged in the public space of the polis seeking a common good. Thucydides recognized that the convulsions that disturbed Greece in the 5th century BC were “such as had occurred and always will occur as long as the nature of mankind remains the same.” (3.82.2) It is he, then, who UNIVERSALIZED the experience of the past, in this case his own recent past.

IN THE BEGINNING : in the Wake of the Persian War

Great wars in history eventually become great wars about history. (Michael Oren , 1999)

This book is about men during war. Of course it was Herodotus who wrote about the allied Greek victories over Persia during the wars of 499-479BC, when Sparta and Athens and Corinth and 29 other Greek poleis fought together for the freedom and independence of the Greek world. Thucydides exists within the afterglow of that conflict, during the Golden Age of Athenian democracy and cultural achievement.

The great military historian John Keegan, in his brilliant book ‘The Face of Battle’(1976), wrote:

What battles have in common is human: the behavior of men struggling to reconcile their instinct for self-preservation, their sense of honor and the achievement of some aim over which other men are ready to kill them. The study of battle is therefore always a study of fear and usually of courage, always of leadership, usually of obedience; always of compulsion, sometimes of insubordination; always of anxiety, sometimes of elation or catharsis; always of uncertainty and doubt, misinformation and misapprehension, usually also of faith and sometimes of vision; always of violence, sometimes also of cruelty, self-sacrifice, compassion; above all, it is always a study of solidarity and usually also of disintegration—for it is toward the disintegration of human groups that battle is directed.

The human factor is uppermost in Thucydides’ text, and an astute reader will look especially for what he has to say about it. Cimon was the last statesman in Athen to attempt to curb the democratic impulse and direct a foreign policy that would avoid a clash with other Greek cities. He failed. Pericles assumed leadership and introduced full democracy and pursued an open policy of imperial expansion.

Since the Persian War, the polis of Corinth had lost its role to Athens as the leading naval power of Greece. Corinth tried to recover her position by expanding her authority across the western coasts and as a first step looked to subjugate a former colony in the region named Corcyra, which held a strategic position of the sea-route to Italy and Sicily. Corinth long resented her Corcyra (today the popular island of Corfu) for failing to pay her the honors due to a metropolis (i.e. Corcyra’s founding city). In 435BC, resentment boiled over into open conflict when the two cities took opposing sides in a civil war in Corcyra’s own colony, Epidamnus. (This war pitted a democratically-minded mob against a group of ruling oligarchs, a situation not uncommon in poleis throughout the Greek world.) Corcyra won an initial naval battle, but Corinth was not prepared to admit defeat and began to prepare a large fleet to sail against Corcyra. Corcyra feared what was coming, but because it had for years pursued a policy of political neutrality, had no allies. The only other state which possessed a navy large enough and experienced enough to help Corcyra counter the Corinthians was Athens.

And so in the spring of 433BC, ambassadors from Corcyra addressed the Athenian Assembly in an attempt to join the Athenian Federation. Their arguments were a clever combination of carrot and stick. They argued : war between Athens and Sparta (leader of the Peloponnesian League) was inevitable; Athens needed to control the seas to maintain its empire; Athens could not allow Corcyra’s fleet to fall into the hands of the Peloponnesian League; having Corcyra as an ally would increase Athenian economic power. Despite the warnings of dire consequences brought to Athens by a delegation from Corinth, and despite the initial hesitation of Athenians to initiate war (i.e. break the sacred truce that existed between the Athenian Empire and the Peloponnesian League), the Athenian citizens voted to provide Corcyra limited support in its war against Corinth by granting a defensive alliance. An Athenian fleet set sail for the waters of western Greece.

When the polis of Potidaea, another former colony of Corinth, but one which WAS a member of the Athenian Federation, attempted to secede, Corinth actively supported it against Athens. This was clear breach of the truce that had been in effect since 445 BC and hostilities began in the northern Aegean. By the terms of the Truce, hostilities should have gone to arbitration. Athens had been careful not to overstep technically the bounds of the Truce.

A NOTE ON SPEECHES

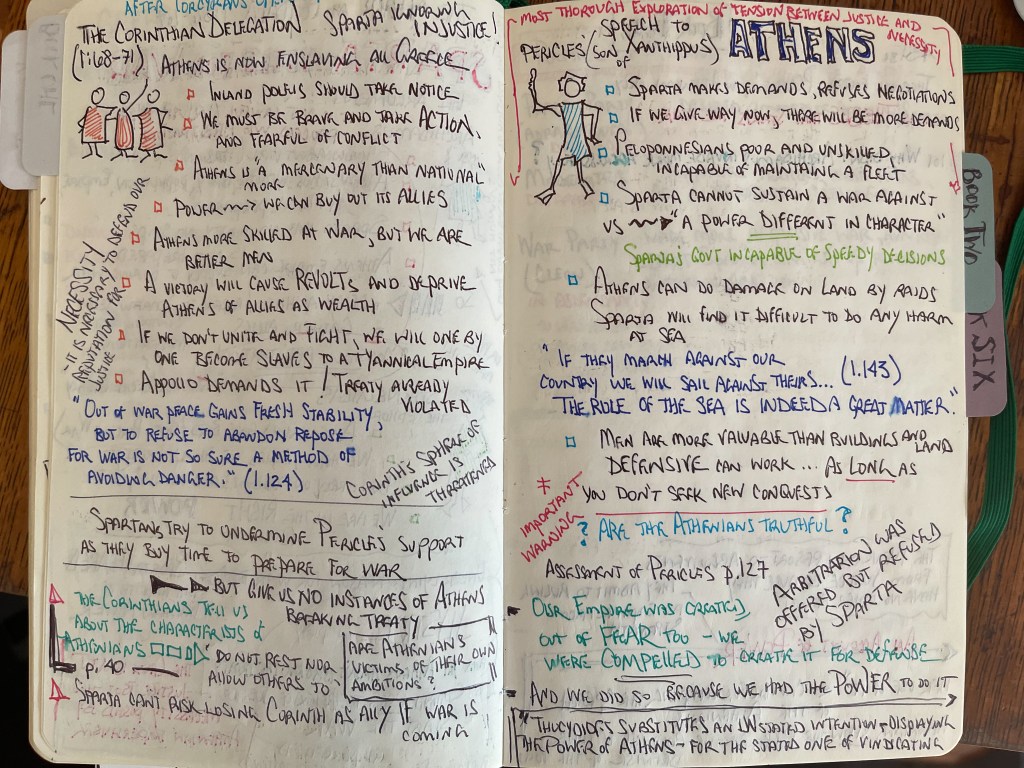

Speeches are an essential ingredient of Thucydides’ method. They make up about 25% of the text and there are some things you need to understand about what Thucydides was doing with them. What you should know: 1) they tend to appear at ‘crossroad’ moments, times when a decision is required 2) they often appear in pairs that represent two sides of a debate (you will benefit from trying to keep a bullet-list of the arguments each presents as part of you annotation), 3) they sometimes are used to reveal the character or inner thinking of a prominent statesman rather than to stand for what was actually said.

The historian Perez Zagorin cautions that we avoid simply identifying Thucydides’ own opinions and judgements with the ones you will find in the recorded speeches. You have to look elsewhere to find Thucydides. Unlike Herodotus, Thucydides strove to report faithfully the substance of what the speakers had actual said or represent opinions appropriate to them. The speeches, therefore, are especially important elements for understanding the substance of the issues in play. You should ALWAYS try to grasp the essence of the argument made by a speech. They are an integral part of Thucydides’ work.

The German philosopher Nietzsche was supremely influenced by the writing of Thucydides. ‘One must read Thucydides line by line,’ he cautioned, ‘and read the thinking hidden behind what he says with as much discernment as his actual words. There are few thinkers who are so rich in thought left unexpressed.’ Consider as you read what ideas Thucydides expresses throughout and HOW he manages to do it.

SOME ADVICE

.

[1] CREATE PROPER ENVIRONMENT

‘Multitasking’ is a myth. Develop sound habits NOW by banishing cell phones and computers from your work-space when you read serious literature. Thirty minutes of focused, uninterrupted reading with benefit you more than a couple of hours of distracted reading. If you care about thinking seriously, YOU MUST get away from your phones and computers and give your brain a little space to work !

It is now proven that intellectual work production degrades for every new mental task added to the thinking environment. It is easy now to live in a state of permanent distraction – and most people who live attached to a cell phone do. You simply MUST wean yourself away from the cell phone and computer screen if you wish to read with any degree of focus necessary to engage with great literature. Here is what Daniel Levitin, distinguished professor of Behavioral Neuroscience, has to say on the topic: “[There is a] metabolic costs [for] multitasking, such as reading e-mail and talking on the phone at the same time, or social networking while reading a book. It takes more energy to shift your attention from task to task. It takes less energy to focus. That means that people who organize their time in a way that allows them to focus are not only going to get more done, but they’ll be less tired and less neurochemically depleted after doing it.” (The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight in the Age of Information Overload, pp. 169-171.)

Daydreaming also takes less energy than multitasking. And the natural intuitive see-saw between focusing and daydreaming helps to recalibrate and restore the brain. Multitasking does not. Perhaps most important, multitasking by definition disrupts the kind of sustained thought usually necessary for problem solving and for creativity.

The idea that you can read or write effectively while carrying on with social media, watching videos, or even listening to music is unsound and wrong-headed. Serious thought, and by extension analytical reading and writing, demand that you turn off your phone and laptop and music device. (I know that may sound rather funny if you are reading this on your computer or phone, but your readings will generally not be online.) This approach will not only benefit your concentration, understanding, and retention (i.e serious education), but will also make you a more efficient reader: 30 minutes of focused reading far outweighs an hour and a half of distracted play-acting at reading.

Cultivate an environment that is conducive to serious intellectual work. While this is really just a subset of the point I made above, its importance demands explication. Find a relatively secluded and quiet space to do your reading. (There’s a reason libraries used to be quiet spaces — I say used to because most libraries now have been polluted by electronic devices, computers, videos, cell phones, etc, that fundamentally disrupt scholarly activity.) Use a desk and a good light. DO NOT read in your bed – or even in your bedroom if you can manage that! Your body reacts to its environment. Laying in a bed tells it that it is time to sleep – and that is exactly what most people who try to read in bed end up doing. [This is why most people read less serious books in bed. It doesn’t really matter much if you fall asleep reading ‘What Ho, Jeeves!’]

[2] SLOW AND THOUGHTFUL

Take your time. Read a few pages at a time and give yourself time for reflection. Think deeply about what you just read. Ask yourself what Thucydides wants to convey. Don’t get lost in the details of the military operations. Acknowledge the central personalities and look for the major arguments. Jot down a few notes that summarize the scene or argument, that articulate the questions you have.

Some of you might recall the four tasks for effective annotation from freshman Cities: 1) What are the main themes and arguments? 2) What essential information (terms) is provided? 3) What questions do I have? 4) Vocabulary (words I need to look up)

“Thucydides is one of those books that disclose themselves only to a kind of reading contrary to every inclination fostered by the ‘information society.’ He requires (to borrow from Nietzsche) readers like cows, readers who know how to ruminate. There is no way to appropriate Thucydides’ thought except by thinking it, by reconsidering the substantive political issues the articulation of which defines his project.” — Clifford Orwin, University of Toronto

[3] BREAK IT INTO SECTIONS

[This is advice for reading the entire work.] The best discussions of major historical events are episodic, i.e. they can be broken into smaller units, each with its own action, themes, personalities, and questions. You will find it helpful to consider each section on its own like a scene in a drama, considering its arguments, personalities, decisions, questions, causes and effects first in isolation. Here is a conventional and helpful breakdown of Thucydides into 5 major sections and I have included some guiding questions to help focus your thinking:

- Book One / reasons for writing background, establishes arguments and themes / why do Athens and Sparta go to war? What are the distinctions made concerning the ‘national character’ of Athens and Sparta?

- Books Two, Three, Four / covers the first ten years of the war / THREE IMPORTANT EPISODES: 1) Mytilene 2) Plataea 3) Corcyra / What are the consequences of the revolutionary conflicts between oligarchies and democracies? NOTE: you may skip Book Four. Focus on reading Books One and Two with intent.

- Book Five / covers 421 to 415 BC The important section is the final scene at Melos.

- Books Six and Seven / covers 416 to 413 BC

- Book Eight / takes us to 411 BC

[4] PURPOSEFUL NOTES

What do you wish to accomplish with your notes? You will, no doubt, answer this question differently for each reading. In this case, you want to asses critically the work of a major historian, comprehending both his method and the main idea he presents in his work. Instead of just writing down undifferentiated bits and pieces, bring some organization to your reading journal. Create sections. Here’s just a few of the organizing sections on my own notes:

- Major Questions Raised and Addressed

- Aphorisms / One-Liners : Thucydides peppers his text with single-line statements that read like philosophical or didactic distillations. Here’s one from book I: ‘Complaints are for friends who make mistakes, accusations for enemies who commit injustices.’ You will find that when you identify and record and think about such statements, they will lead you to deep insights into Thucydides’ ideas. Keeping a list of these as you read is imperative if you wish to have a sense of the depth of his writing/ideas.

- Follow just a few People: you will read a ton of names; only a few are really worth thinking deeply about on a first read. Here are the main ones: Pericles, Nicias, Alcibiades, Cleon Archidamus, Sthenelaidas, Brasidas,

[5] READING ‘GREAT LITERATURE’ IS DIFFERENT

You should read ‘great books,’ those such as Thucydides’ History that have achieved special status, differently from the way you approach other works. Active reading MUST be cultivated. That means stay awake, ask questions, and write while reading – on the text and in a reading journal optimally. Here are a few questions that serious readers always consider as they work through texts:

- What is the writing about? Can you summarize it in your own words (if yes, WRITE that summary in your notes or in the margins)?

- What problem/issue is the author addressing or trying to solve?

- What questions does the author wish to press upon his/her reader?

- What are the author’s propositions (theses)?

- What of it? Are they true?

- Should the author be believed?

- How does the text relate to the period in which it was written?

- How does the text relate to others writings on the same topic?

- How does the text challenge your own notions of the topic?

- What questions come to mind as I read this document?

To paraphrase Mortimer Adler, one of the founders of the Great Books Program, great ideas seek truth and must be discussed seriously. They demand more than idle chit-chat. Reading for enlightenment demands your full attention and engagement. Good readers carry on a dialogue with their books and will have a collection of written notes (reactions, ideas, and questions) afterward. This is why I encourage you all to begin reading journals of your own, something that is separate, and entirely different, from informational class notes. Effective reading requires work and skill. Spark Notes or a Wiki article WILL NOT lead to an enlightened understanding of a text.

The only books worth reading this way are the books over your head. The Great Books are the books that are worth everybody’s reading because they are over everybody’s head all the time.

Mortimer Adler

IMPORTANT WORD ON NOTE-TAKING

Avoid getting bogged down with detailed notes. Your ideas and Thucydides’ ideas are more important than details of the war. You want to have notes that 1) sum up major arguments/themes 2) refresh your memory about questions you had while reading or the connections you made to other texts or situations 3) capture some key quotations, and 4) provide page numbers so you can return to the text during discussion.

You must be logged in to post a comment.