The events in this account happened more than 40 years ago. I was a teenager at the time, and what few notes I had made were destroyed in the air raids….While I cannot vouch for the accuracy of every name and date, what I am sure of is that this is how I experienced Nazi Germany.

In Hitler’s Germany, my Germany, childhood ended at the age of 10, with admission to the Jungvolk, the junior branch of the Hitler Youth. Thereafter, we children became the political soldiers of the Third Reich. In reality, though, the basic training of almost every child began at six, upon entrance to elementary school. For me that year was 1933, three months after Adolph Hitler was appointed Chancellor. I have only a child’s recollection of the early years of his rule, but I vividly remember the wild enthusiasm of the people when German troops marched through my hometown on 7 March 1936, in the process of taking back the Rhineland from the hated French, whose soldiers had left in 1932….

Under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, the Rhineland had not only been demilitarized, but placed under French occupation for 15 years. France, and to some degree the unprotesting British, handed Hitler the first of his bloodless victories by allowing fewer than 3000 German troops to re-enter the region unchallenged by France’s vastly superior army. There would be much more appeasement (Sudetenland, Austria, Czechoslovakia) enough to convince Hitler that he had become invincible, and that he could attack Poland with impunity. That turned out to be a delusion which cost more than 50 million lives.

None of this, of course, was apparent to the people of Wittlich [Heck’s hometown] in 1936. On that March evening, perched ont he shoulders of my Uncle Franz, I watched a torchlight parade of brown-shirted storm troopers and Hitler Youth formations, through a bunting-draped marketplace packed with what seemed to be the whole population….On that evening, Hitler surely symbolized the promise of a new Germany, a proud Reich that had once again found its rightful place. Unlike our elders, we, the children of the ’30s, knew nothing of the turmoil or freedom of the Weimar Republic. As soon as the Nazi regime came to power, it revamped the educational structure from top to bottom, and with very little resistence….We five and six-year-olds received an almost daily dose of nationalistic instruction, which we swallowed as naturally as our morning milk. Even in working democracies, children are too immature to question the veracity of what they are taught by their educators. Unless they have singularly aware parents, the very young become defenseless receptacles for whatever is crammed into them. We never doubted for a moment that we we fortunate to live in a country of such glowing hopes.

… To us innocents in the Hitler Youth, the Jews were usually proclaimed as devious and cunning over-achievers, especially in their aim of polluting our pure Aryan race, whatever that meant….On the cool, windy afternoon of 20 April 1938, Adolph Hitler’s 49th birthday, I was sworn into the Jungvolk. Since 1936, the Hitler Youth had been the sole legal youth movement in the country, entrusted with the education of Germany’s young; but it was still possible not to belong. The following December, 1939, the Reich Youth Service law made membership compulsory for every healthy German child over nine. That meant Aryan children, only, of course. Severely handicapped children could not belong, even if their parents happened to be fanatic Nazis. At the time retarded children and adults were killed in the euthanasia centers which the regime had quietly established. Here the so-called ‘useless eaters’ were put to death by injection or gas. The was the testing ground for an efficient method that would soon exterminate millions in near total secrecy. [the extermination camps weren’t exactly secret, but…]

When I was sworn into the Jungvolk, I had been thoroughly conditioned, despite my Catholic upbringing, to accept the two basic tenents of the Nazi creed: belief in the innate superiority of the Germanic-Nordic race, and the conviction that total submission to the welfare of the state — personified by the Führer — was my real duty….Adolph Hitler ceaselessly encouraged the feeling that we were his trusted helpers and used it with brilliant intuition.

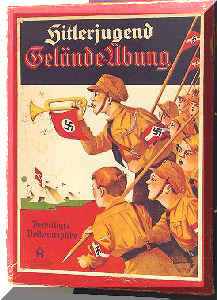

…Like most 10-year olds, I craved action, and the Hitler Youth had that in abundance. Far from being forced to enter the ranks of the Jungvolk, I could barely contain my impatience and was, in fact, accepted before I was 10. It seemed like an exciting life, free from parental supervision, filled with “duties” that seemed sheer pleasure. Precision marching was something one could endure for hiking, camping, war games in the field, and a constant emphasis on sports…. Many of our parents did not like the idea of that all-encompassing camaraderie with social inferiors [rigid class distinctions still existed in Germany]; but that only heightened our sense of alienation from our elders, who eventually became afraid of us, or more correctly, of the power we wielded.

The first friend of my childhood was Heinz Ermann, whose parents had a cattle business just up the street from us….I was fascinated by Siegfried’s [Heinz’s uncle] wooden leg, a remembrance of the 1916 Battle of the Somme, where he had earned the Iron Cross I Class for conspicuous bravery. He was proud of his service to the Fatherland; but as it turned out, the Fatherland was not proud of him. Just 13 years after he showed me how to play marbles and sit correctly on a horse, Siegfried and the whole Ermann family were gassed in Auschwitz for being Jewish “subhumans.”

… Even before it became the official policy of the government, he [Heck’s elementary teacher, Herr Becker] had never hidden his conviction that the Jews were “different” from us. But this prejudice, shared by millions of Germans, quickly turned to outright hatred after the promulgation of the Nuremburg Racial Laws of Spetember 1935. From then on, Jews were no longer legal German citizens, but members of an inferior, alien race despite their impressive achievements. Herr Becker demonstrated to us in his weekly “racial science” instruction how and why they were different. “Just observe the shape of their noses,” he said, “…although some have obstructed such tell-tale signs by their imfamous mixing with us.” I thought then that Heinz must have been very successful at this “mixing”: he looked very much like any of us, and certainly more Germanic than I with my French blood. In Heinz’s case, I knew it wasn’t a Jewish trick, but I wasn’t so sure about the others.

Strangely, Herr Becker seldom beat Jewish children like he whipped us. Instead, he made them sit in a corner, which he sneeringly designated as “Israel.” We quickly realized that he wanted us to despise the Jews. It was the first time I had experienced discrimination, and it bewildered me…. One day I asked Heinz why his ancestors had killed Jesus, and after some frowning he shrugged: “I sure don’t know. He was one of us, but I htink the Romans did him in. He wanted to be king.” It seemed like a good reason, and it ended our interest in the strange ways of religion until we met Herr Becker who was both pious and patriotic.

With a callousness of youth, I forgot Heinz pretty fast. Herr Becker announced the removeal of the Jewish pupils by saying, “They have no business being among us true Germans.”… Despite occassional pangs of guilt, I visited Heinz less and less at home, especially since Uncle Siegfried no longer joked with me…. I never lumped Heinz in with the “bad” Jews, who were determined to do us in with the help of the Bolsheviks, but I never mentioned his name either. Later when I had to undergo character interviews in the Hitler Youth prior to promotions, I always denied having associated with a Jew even at the age of seven. I readily admitted that I did not consider my father to be an eager National Socialist, a question that always came up in family background checks. I instinctively realized that such admission could not hurt my career. Quite to the contrary: it was a measure of one’s dedication to prevail against parental indifference or hostility. To feel anything but disdain for a Jew, however, would have aroused suspicion.

… My family belonged to the many apolitical Germans who became impressed not with Hitlers’ political ideology, but with his undeniable success in restoring full employment and economic order as well as social stability to a devastated, beaten-down nation which suffered from a massive inferiority complex…. “You’ve got to hand it to Hitler,” said my grandmother, who equated idleness with villainy, “he talks big, but he puts everybody to work, even the damned gypsies.” One must not forget that the depression of the 1930s was the country’s second such calamity within a decade. In December of 1923, a single US dollar could be exchanged for 4.2 billion marks…. Millions of Germans bartered away everything they had, including their dignity; thousands of women turned to prostitution to feed their families. Inflation and unemployment not only ravaged their traditional victims in the working class, but wiped out much of Germany’s middle class as well. Such work-obsessed people as the Germans, traditionally obedient to a king and kaiser, could forgive a leader nearly anything, including a little harassment of a disliked minority, if he provided economic stability. That, in essence, was Hitler’s strong appeal.

… The Wehrmacht [the regular German Army] always strove for cordial relations with the Hitler Youth for the obvious reason that we were its pool of future manpower. The name of the slim and friendly colonel, who was then the top liaison officer for youth affairs in the Wehrmacht didn’t mean anything to us, but just five years later the world would know him as Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the “Desert Fox.” Even then he projected a sense of camaraderie, tempered with some reserve, which made him a soldier’s soldier, similar to the American General Omar Bradley. Although he later despised Hitler, the pre-war Rommel was a dedicated Nazi.

CHAPTER 2

… Each September in Nuremburg, seemingly all of Germany went on a seven-day nationalistic binge [the Nazi Party Congress] that inspired the nation and stunned the rest of the world…. Nuremburg, the medieval showcase of Germany, with its history of the Meistersinger and Albrecht Dürer, had been the site of the congress since 1927, precisely because its architecture appealed to the nationalistic instincts of all Germans. Its castle, gates and turrets were the ideal mystical backdrop for emotion-laden spectacles whose leitmotif was German greatness…. Of all the Nazi organizations, the Hitler Youth was, by far, the most naively fanatical. We had no political past. Most of us looked with a good measure of disdain upon the average party member, fat and bourgeois, who usually joined to further his miserable career. Ours was the only one of the party branches with the right to address Adolph Hitler with the familiar Du, although I knew of noboday who had ever done that outside of a poem to the Führer.

Hitler knew that we were essential for the future of his movement, and he instilled in us the immensely flattering conviction that we were his most trusted vassals….We never had a chance. I am sure none of us in that audience took our eyes off him. I don’t recall the exact content of the speech 45 years later, but I’ll never forget its emotional impact…. We simply became an instrucment in the hands of an unsurpassed master. His right fist punctuated the air in a staccato of short, powerful jabs as he roared out a promise and an irresistible enticement. “You ,my youth,” he shouted, with his eyes seemingly fixed on me, “are our nation’s most precious guarantee for a great future, and you are destined to be the leaders of a glorious new order under the supremacy of National Socialism!” He then paused and lifted both arms in a gesture of triumphant benediction. “You, my youth,” he screamed hoarsely, “never forget that one day you will rule the world!” We erupted into a frenzy of nationalistic pride that bordered on hysteria. For minutes on end, we shouted at the top of our lungs, with tears streaming down our faces: “Sieg Heil, Sieg Heil, Sieg Heil!” From that moment on, I belonged to Adolph Hitler body and soul.

…No one who ever attended a Nuremburg Reichsparteitag can forget the similarity to religious mass fervor it exuded. Its intensity frightened neutral observers but it enflamed the believers…. On th ebricjkw all enclosing Herr Becker’s school had been a huge white-washed inscription that read: “The Jews are the traitors to Germany and our misfortune.” By 1938, I didn’t have the slightest doubt that this was true. Herr Becker and his history lessons depicting the Communist-Jewish infamy beginning even during World War One, had prepared me well, long before the Hitlerjungend knew I existed.

On the afternoon of 9 November 1938 [Kristalnacht], I watched open-mouthed as small troops of SA and SS men jumped off trucks on the market place, fanned out in several directions, and began to samsh the windows of every Jewish business in town. I didn’t know any of the men, but Paul Wolff, a local carpenter who belonged to the SS, led the biggest troop and pointed out the locations. One of their major targets was Anton Blum’s shoe store next to the city hall. Shouting SA men threw hundreds of pairs of shoes into the street. They were picked up [i.e. stolen] in minutes by some of the nicest people in our town.

We were on our way home from school, and four or five of us followed Wolff’s men when they headed up the street towards the synagogue. Groups of people watched silently, but many followed just like we did. When the signing gang reached the synagogue, they broke into a run and literally stormed the entrance. Seconds later, the intricate lead crystal window above the door crashed into the street, and pieces of furniture came flying through doors and windows…. The brutality of it was stunning, but I also experienced an unmistakable feeling of excitement.

…

Even Herr Becker never claimed that all Jews were equally guilty for the past misfortunes of Germany. Still the radical Communist leaders of 1919, especially the infamous Karl Liebknecht, head of the Spartacusbund, who had nearly succeeded in turning Berlin itself into a Soviet republic, were very often Jewish. “This sinister servant of Moscow,” Herr Becker disclaimed in an angry voice, “had already agitated against the Fatherland when we were dying in the trenches of France. The men who killed him and his depraved Jewish associate (the Polish-born Roas Luxenburg) did God’s work in the name of Germany.”

…Herr Becker wasn’t the only one afraid of the Communist menace. Shortly after the events of Kristalnacht of November 1938, my father, who was on the farm for a visit, said bitterly that his party, the Social Democrats, had handed Hitler Germany on a silver platter because they hated their fellow workers’ party, the Communists, more. I didn’t understand exactly what he meant at the time. In retrospect, I think it was the last time my father riled against the regime in front of me. It was his fortune that I began to consider him and uneducated, unpatriotic loud-mouth. He wasn’t much of a drinker, but when he had a few too many, he had a tendency to shout down everyone else, not a small feat amoung the men of my family. “You mark my words, Mother,” he yelled, “that goddamned Austrian housepainter is going to kill us all before he’s through conquering the world.” And then his baleful ete fell on me. “They are going to bury you in this goddamned monkey suit, my boy, ” he chuckled, but that was too much for my grandmother. “Why don’t you leave him alone and watch your mouth; you want to end up in the KZ [concentration camp]?” He laughed bitterly and added: “So, it has come that far already, your own son turning you in?” My grandmother told me to leave the kitchen, but the last thing I heard was my father’s sarcastic voice. “Are you people all blind? This thing with the Jews is just the beginning.”

…

It’s astonishing how easily the Hitler Youth exacted obedience. Traditionally, the German people were subservient to authority and respected their rulers as exalted father figures who could be relied upon to look after them. A major reason why the Weimar Republic, despite its liberal constitution, did not catch on with many Germans, was the widespread impression that no one seemed to be firmly in charge. Hitler used that yearning for a leader brilliantly. From our very first day in the Jungvolk, we accepted it as natural law — especially since it was merely an extension of what we had learned at school — that a leader’s orders must be obeyed unconditionally, even if they appeared harsh, punitive or unsound. It was the only way to avoid chaos. This chain of command started at the very bottom and ended with Hitler…. There was a certain amount of juvenile delinquency, but, by today’s standards, very little. The punishment was too harsh. It could, for instance, lead to expulsion from the Hitler Youth, which would be the end of any meaningful career, since it stamped the offender as politically unreliable.

… The sun-speckled summer of 1939, with all its promise of a carefree life, ended on 1 September….I could hear the radio from the kitchen below. It was never turned on that early. There was a sudden fanfare blast of a special bulletin on the national radio network. “What’s going on?” I asked, and then saw the tears in my aunt’s eyes. “Our troops went into Poland thsi morning,” she replied. “We are at war.”

“Its about time,” I said, “the Polacks have mistreated our people much too long.”

“Why don’t you keep your mouth shut you damned idiot,” she screamed. “Don’ t you know that hundreds of good men are dying this hour?” I looked at her in consternation because her fury was genuine. [Heck’s aunt had become engaged to a German soldier who had been stationed on the Polish frontier.]… my aunt’s reaction was typical of most Germans on that day. Far from the wild exuberance which greeted the outbreak of WWI, the invasion of Poland cast apprehension and fear in the hearts of our people. Unlike their Führer, the German masses were not eager to wage war. The last war with its terrible bloodletting was still fresh in the memory of many families, including ours. My Uncle Joseph had been the last soldier of Wittlich to lose his life in 1918. He was shot through the head by a sniper three days before the end of the war. But soon the initial feeling of dread dissipated, with news of the astonishing victories of the Blitzkrieg. As usual, the Führer was bourne out in his conviction that our army was invincible. But the era of Hitler’s incredible, bloodless conquests had come to an end, and with it my carefree childhood.