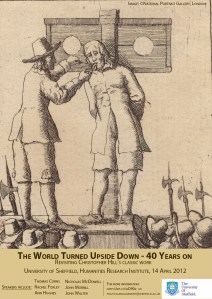

The following is an excerpt from Christopher Hill’s massively influential The World Turned Upside Down, first published in 1972.

The essence of feudal society was the bond of loyalty and dependence between lord and man. The society was hierarchical in structure: some were lords, others were their servants. ‘Whose man art thou?’ demanded a character in one of Middleton’s plays. The reply, ‘I am a servant, yet a masterless man, sir,’ at once produced an incredulous retort, How can that be?’ By the 16th century society was becoming relatively mobile: master less men were no longer outlaws but existed in alarming numbers — 13,000, mostly in the North [of England], a government inquiry calculated in 1569; 30,000 in London alone, it was guessed more widely in 1602. Whatever their numbers such men — servants to nobody — were anomalies, potential dissolvents of the society.

First, there were rogues, vagabonds and beggars, roaming the countryside, sometimes in search of employment, too often mere unemployable rejects of a society in economic transformation, whose population was expanding rapidly…. The fluctuations of the early capitalist cloth market brought wealth to a fortunate few, ruin to many. The inefficient and the unlucky went to the roads. They caused considerable panic in ruling circles during the 16th century, but they were never a serious menace to the social order. Vagabonds attended no church, belonged to no organized social group. For this reason it seemed almost self-evident to Calvinist theologians that they were ‘a cursed generation’. Not until 1644 did legislation [in the Long Parliament] insist that rogues, vagabonds and beggars should be compelled to attend church every Sunday….

Secondly there was London, whose population may have increased eight-fold between 1500 and 1650. London was for the 16th-century vagabond what the greenwood had been for the medieval outlaw — an anonymous refuge. There was more casual labor in London than anywhere else, there was more charity, and there were better prospects for earning a dishonest living. In the late 16th and early 17th centuries men suddenly became aware of the existence of a criminal underworld. Its apparent novelty perhaps caused it to be over-publicized: it was no doubt far less important than the world of dock labor, watermen, building laborers and journeymen of all sorts who had no hope of becoming masters. What matters for our purposes is the existence of a large population, mostly living very near if not below the poverty line, little influenced by religious or political ideology but ready-made material for what began in the later 17th century to be called ‘the mob’….

A quite different sort of masterless men were the protestant sectaries. These had as it were chosen the condition of masterlessness by opting out of the state church, so closely modeled on the hierarchical structure of society, so tightly controlled by parson and squire. Sects were strongest in towns, where they created hospitable communities for men, often immigrants, who aspired to keep themselves above the level of casual labor and pauperism: small craftsmen, apprentices, serious-minded laborious men, all could recognize each other as the elect in a godless world…. Such men were highly motivated, and they carried to its logical conclusion the principle of individualism which rejects all mediators between man and God. From the circumstances of their life in vast anonymous cities and towns they had escaped from feudal lordship. The bond of their unity was a common acceptance of the sovereignty of God, against whose wishes no earthly loyalty could be weighed….

Fourth among our masterless men are the rural equivalents of the London poor — cottagers and squatters on commons and wastes and in the forests. Like our first two categories, these were the victims of the rapid expansion of England’s population in the 16th century; sometimes the victims, sometimes the beneficiaries of the development of new or the growth of old industries. Unlike the relatively stable and docile population of open arable areas, these men, cliff-hanging in semi-legal insecurity, often had no lords to whom they owed dependence or from whom they could hope for protection….

Fifthly was the itinerant trading population, from pedlars and carters to badgers, merchant middlemen. It has been suggested that these wayfarers, linking heath and forest areas, may have helped to spread radical religious views… . Scottish Covenanters in the 1630s were alleged to have used traveling merchants ‘to convey intelligence and gain a party in England’. Certainly the Privy Council was worried about carriers in 1637-8. Country inns and taverns used by itinerants were noted as centres for news and discussion. In the civil war, Professor Everitt observes, troops were normally billeted in the inns of provincial towns.

—-

Professor Walzer has suggested that Puritan insistence on inner discipline was unthinkable without the experience of masterlessness. Their object was to find a new master in themselves, a rigid self-control shaping a new personality. Conversion, sainthood, repression, collective discipline, were the answer to the unsettled condition of society, the way to create a new order through creating new men…. Beneath the surface stability of rural England, then, the vast placid open fields which catch the eye, was the seething mobility of forest squatters, itinerant craftsmen and building labourers, unemployed men and women seeking work, strolling players, minstrels and jugglers, pedlars and quack doctors, gipsies, vagabonds, tramps: congregated especially in London and the big cities, but also with footholds wherever newly-squatted areas escaped from the machinery of the parish or where labor was in demand. It was from this underworld that armies and ships’ crews were recruited, that a proportion at least of the settlers of Ireland and the New World were found, men prepared to run desperate risks in the hope of obtaining the secure freehold land (and with it, status) to which they could never aspire in overcrowded England….

The eternally unsuccessful quest by JPs to suppress unlicensed ale-houses was in part aimed at controlling these mobile masses, which might contain disaffected elements, separatists, itinerant preachers…. It was logical, if not unnaturally resented, for JPs to use the same procedures against itinerant ‘Messiahs’, Quaker missionaries and Baptist tinkers as against vagabonds. The Vagrancy Act of 1656 was directed against ‘all wandering persons’; the Quakers complained that it would have taken hold of Christ and the Apostles.

___

A collection of masterless men whom I did not consider in the last chapter — the most powerful, the most politically motivated, but also the shortest-lived — was the New Model Army.